There is nothing a human being likes better than a mystery. Even artistic judgment plays second fiddle to our appetite for a good secret. Artists have always known that besides delighting us with their skill, they can tease us into interest in their work.

Just think of the intrigue and excitement that Dan Brown created with his book The Da Vinci Code. He was benefitting from the centuries of mystery the painter Leonardo da Vinci had already stirred up around his Mona Lisa with his unknown sitter, her ambiguous smile and the mysterious numbers apparently visible in her eyes when scrutinised under a magnifying glass.

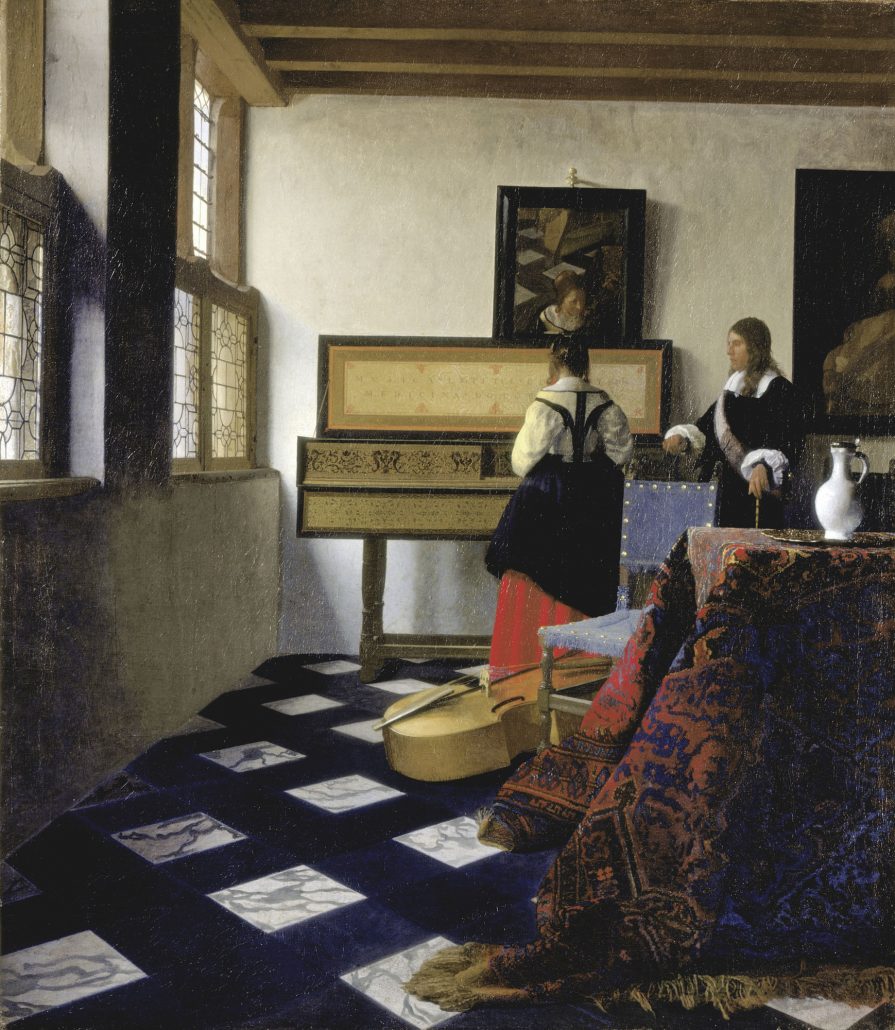

Paintings have always been carriers of secret messages. There is the trail of iconography that would have led the devout in medieval Cathedrals to understand the stories depicted in stained glass windows. There are the Dutch paintings of the 17th century, with their sly illusions to hidden lust. Take Johannes Vermeer’s The Music Lesson. A young girl is being taught to play the virginals by a handsome tutor; an apparently sober scene of bourgeois decorum. The white wine pitcher in the foreground, however, suggests an atmosphere of intoxication, while the mirror reveals that the girl is looking at her tutor, not her hands, as she plays.

The Music Lesson by Vermeer

In other paintings, scenes of domestic tranquility are disturbed by figures carrying letters, which we imagine may contain news that will detonate the calm. In his painting The Slippers, Samuel van Hoogstraten paints an apparently innocent still life of two slippers on the floor of a hall. On the wall, however, he has painted in a copy of a famous painting, Father Admonishing His Daughter by Caspar Netscher, which is set in a brothel. His original audience would have picked up the reference, recognised the slippers as being an odd pair, one female and one male, and made the inference.

There are then the art works that disappear and are rediscovered. It seems our delight in them is many times multiplied. The popularity of the public campaign to raise funds (£34.9 million) for the National Gallery in London to buy Raphael’s painting The Madonna of the Pinks was at least partly owing to the painting having languished incorrectly labelled in the collection of the Duke of Northumberland for more than a century. It was the splendour of the frame that tipped off the Renaissance scholar Nicholas Penny, later director of the National Gallery, that the painting must be an original.

The British television series Fake or Fortune? capitalises on our eagerness to know more about the pictures that confront us. Are they by the artists to whom they are attributed? What is the story they tell? In one programme, the presenters Philip Mould and Fiona Bruce set out to prove that a painting of a man in a black cravat was one of the first pictures ever painted by celebrated and controversial British artist Lucian Freud, even though Freud himself denied painting it. Part of our excitement, of course, is the difference in value that attribution would make.

And then there are the discoveries that modern science has made possible. The luxuriously decadent Bacchus by Italian painter Caravaggio, with its ruddy cheeked God, languidly posed with extravagant headdress and full glass of wine, conceals the artist’s self-portrait. It is cheekily inserted as a reflection submersed in the wine bottle, a revelation made possible only with infrared technology.

In 2012, while cleaning Picasso’s haunting 1904 painting Woman Ironing a conservator at the Guggenheim Museum discovered, using two types of infrared cameras — hyper-spectral and multi-spectral – a portrait of a man lurking beneath the painted surface. Since then, speculation has ranged widely about who the young man might be – increasing public interest in an already much-loved painting.

Two years later, a conservator at the private Phillips Collection in Washington DC detected a painting of a bearded man beneath Picasso’s 1901 work The Blue Room. Since then, the team has been trying to gather as much information about its composition as possible, using fluorescence spectroscopy. Dorothy Kosinski, director of The Phillips Collection, said at the time: “Our audiences are hungry for this. It’s kind of detective work. It’s giving them a doorway of access that I think enriches, maybe adds mystery, while allowing them to be part of a piecing together of a puzzle.”

Banksy Swat Van

The master of mystery has to be the graffiti artist Banksy. Many graffiti artists are anonymous – the nature of their work is often illegal and the persona requires a degree of subterfuge. Banksy, however, has turned elusiveness itself into an art form, which adds thousands to the value of his works. He became famous after a series of so-called guerrilla stunts during which he painted the West Bank barrier and put an inflatable figure of a Guantanamo Bay prisoner at Disney World.

In 2009, visitors queued around the block for Banksy’s retrospective at the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery. Excitement was whipped up by the notion that the artist himself had helped install the show, in secrecy, with only a handful of people aware that the show was taking place until the day before it opened.

Even his works disappear. A spray-painted S.W.A.T. van vanished after Bansky exhibited it just once, in a downtown industrial lot in Los Angeles at his first US solo show Barely Legal, attended by such Hollywood aristocracy as Brad Pitt, Angelina Jolie, Cameron Diaz, Jude Law and Dennis Hopper. It reappeared this summer at Bonhams auction house where it sold for £218,000.

By Emma Crichton-Miller