By Mavis Teo

Before Tibet came under Chinese rule in 1951 and was officially named as Tibet Autonomous Region in recent years, it laid claim to more land, including Yunnan and parts of Southwest China. Part of this land included an area dense with verdant vistas and ragged mountain ranges, which was immortalised in novelist James Hilton’s Lost Paradise as the magical “Shangri-la”. Today Tibet still inspires with its exotic beauty in a vast, untameable landscape that rises to over 6,000m above sea level at the Himalayan border it shares with Nepal.

Having read Hilton’s book as an impressionable child, I have always dreamt of visiting this heaven on earth. It would be a completely different world from the places I have been. Despite the negative feelings many Tibetans and some foreigners have of Chinese control over Tibet, it is an undeniable fact that the Chinese government has made travelling in a country larger than Western Europe easier. The 1,956km long Qinghai-Tibet railway completed in 2006 which includes the world’s highest track at 5,072m high has enabled many tribes of Tibetan ethnicity in China to visit some of the centuries-old monasteries which they consider as must-visits in one’s lifetime as a Buddhist. Highways have now made it possible for land cruisers to transport tourists from Europe and the US in relative comfort across challenging terrain. Despite the interruptions to international tourism (read: bans) caused by incidents of self-immolation carried by independence activists, tourism grew by 22% in 2013, with a record of 12.91 million visitors.

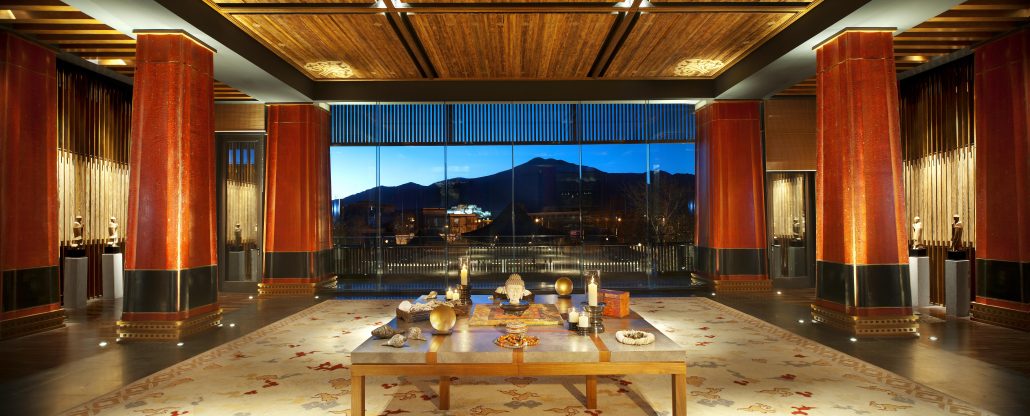

In 2010, renowned luxury hotel group St Regis opened in Lhasa, Tibet’s capital, with three restaurants, an uber-luxe spa and views of the Himalayas and Lhasa Valley amongst many things. Since then, Shangri-la and Intercontinental have opened in the city. Assured that these luxe openings could mitigate any discomfort I have in Tibet, I decided to embark on my Tibetan voyage through an agency, Country Holidays. Armed with a lot of advice on how to combat altitude sickness, I set off for Tibet as a leisure visitor.

At 3650m above sea level, the first signs I had of being in a different world upon landing in Lhasa was light-headedness. Though my condition – mostly breathlessness after some trekking uphill was considered mild, it was to last for the next three days. Fortunately, I was in the hands of a very experienced local guide and driver who made sure I was well taken care of during my entire 6-day trip which would cover Lhasa, Gyantse and Shigatse in central Tibet. I started my sightseeing at Lhasa’s most famous monument, the Potala Palace, a UNESCO world heritage and former palace of the 14th Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibet who fled to India in exile in 1959. While the government has gazetted the building which was built in the 17th century as a museum, the locals still revere the palace as a holy place. On a crisp November morning, I saw scores of Tibetans from different regions in Tibet and China, distinguished by the colours of their robes and the complexity of their headdresses heavy with amber and turquoise stones, trudging wearily but purposefully to the Palace. Once there, they shuffle from room to room, chanting mantras, turning prayer wheels and lighting yak butter candles. The sight of a blind old lady being helped up by her family as they climbed up the hill to the 13-storeyed high architecture with 5-metre thick walls protecting 1,000 rooms full of sculptures, painted walls and relics, moved me.

At Jokhang monastery, a stone’s throw away from St Regis where I was staying, I saw a part of Tibetan life that has escaped Chinese capitalism. The streets of Bokhor Circuit which surround the temple are crowded with devout Buddhists, some who have travelled thousands of miles by crawling and prostrating, which will take at least seven months. The Circuit is also where Tibetans do their circumambulation rounds in a clockwise direction from dawn to dusk, which they believe will redeem their souls for the next life. It now also houses many shops in old Tibetan buildings with narrow windows, colourful ties and Tibetan prayer flags, selling mostly faux precious stones and antiques of questionable authenticity. Johkhang itself houses an ancient Buddha that was carried to Lhasa 1,300 years ago from the ancient Chinese capital of Changan, now Xian. At the 15th century Sera monastery, I witnessed a fiery debating session among monks who meet daily to discuss topics touched upon in their books.

After Lhasa, I was to go on a six-hour road trip to Gyantse and then Shigaste. Tiring as it may sound, the road trip was one of the most unforgettable experiences I’ve had so far in my life – it is also the only way to experience the beauty of the Tibetan landscape. In early winter, the jagged mountainscape is mostly a palette of slate, taupe and sand with the snow-capped Himalayas in the background. We drove past three passes, ranging from 4330m to 5039m above sea level; the most memorable of which was the Kampa-La. It offers spectacular views of the turquoise Yamdrok Lake to the south, and the glistening Brahmuputra River that connects to Nepal to the north. Along the way, we would occasionally come across barley fields and herds of yaks and cows grazing. The Tibetan menu is simple. The locals eat mostly for subsistence and meals mostly consist of yak butter tea, yak stews or curries and barley flour noodles. Fortunately, there are some restaurants in major cities that cater to foreigners by providing Western, Chinese and Nepalese options on the menu.

At the dusty old town of Gyantse, I visited Pelkor Chor. Next door to it is the Kumbum, a white stupa, with a tiered dome and four sets of painted eyes, each gazing out in a different cardinal direction to represent Buddha’s omniscience. Kumbum means “100,000 images” represented by the many paintings of demons and deities in the chapels.

En route back to Lhasa nearing the end of my trip, I stopped by Shigatse, Tibet’s second largest city and also home to Tashilungpo, the seat of Panchen Lama, second in command to the Dala Lamai. The most important room to visit is the Maitreya Chapel with a 25m tall statue of the future incarnation of Buddha, made with 300kg of gold and precious gems.

Tibet is not a place for luxury. Tibet is not the place for the high-end traveller who wants flawless service at classy restaurants and pristine restrooms at every stop. Tibet is a place on the destinations bucket-list of the well-read reader who has had her fill of luxury trips in cities with a developed tourist infrastructure and manicured cityscapes. Tibet offers an experience in an open wilderness still largely devoid of the skyscrapers and industries in modern cities, where people might be more efficient but less warm and sincere than the Tibetan villagers who don’t have much materially, but would offer you a warm yak butter tea because you are shivering in the cold. In Tibet, you are reminded of how small you, a human being is in a universe that looks infinite in its vastness, and how at the end of the day, it’s not what people have that touches you, but the little acts of kindness from random strangers.